While concerns about the debt ceiling have been increasing, markets, businesses, and the economy are likely to see only minimal impact until we are days, or maybe a few weeks, from the “x date,” the date on which the federal government will no longer be able to meet all its obligations, likely in the summer or early fall. We continue to believe the chances that Congress will fail to raise the debt ceiling before the x date remain extremely low, but current political dynamics have likely increased the risk and there are some negative consequences to even an eleventh hour agreement, as we saw in 2011.

Debt ceiling drama is once again increasing, but the build-up will be slow. The Department of the Treasury (Treasury) has been using “extraordinary measures” to cover debt payments since January 19, but that has not been an unusual course of action and does not impact the government’s ability to function smoothly. Markets, businesses, and the economy are likely to see only minimal impact from the debt ceiling debate until we are days, or maybe a few weeks, from the “x date,” the date on which the federal government will no longer be able to meet all its obligations. That date will likely be in the summer or early fall, depending on tax receipts and other factors.

We continue to believe the likelihood the debt ceiling won’t be raised in time remains extremely low. Nevertheless, uncertainty about whether it will be raised can have its cost. We believe those costs are currently near negligible and will build slowly. Risks will increase more quickly if we are several weeks away from the x date and still appear to be at a deep political impasse. The mere appearance of Democrats and Republicans playing politics near the deadline can weigh on markets and force businesses to start preparing for the very unlikely, but still possible, outcome of a government default. The current political dynamics, with a split Congress and a thin majority in both the House and Senate, have likely increased the overall risk and there are some negative consequences to even an eleventh hour agreement, as we saw in 2011.

U.S. Debt Ceiling Questions Answered

1. What is the debt ceiling?

The debt ceiling is the limit on how much the federal government can borrow. Unlike every other democratic country (except Denmark), a limit on borrowing is set by statute in the U.S., which means Congress must raise the debt ceiling for additional borrowing to take place.

2. Why does the U.S. do it differently?

The debt ceiling was originally created to make borrowing easier by unifying a sprawling process for issuing debt to help fund U.S. participation in World War I. The process was further streamlined to help fund participation in World War II, creating the debt ceiling process that is in use today. According to the Constitution, Congress is responsible for authorizing debt issuance, but there are many potential mechanisms that could make the process smoother.

3. Why is it important to raise the debt ceiling?

The government uses a combination of revenue, mostly through taxes, and additional borrowing to pay its current bills—including Social Security, Medicare, and military salaries—as well as the interest and principal on outstanding debt. If the debt ceiling isn’t raised, the government will not meet all its current obligations and could default.

4. Has Congress always raised the debt ceiling?

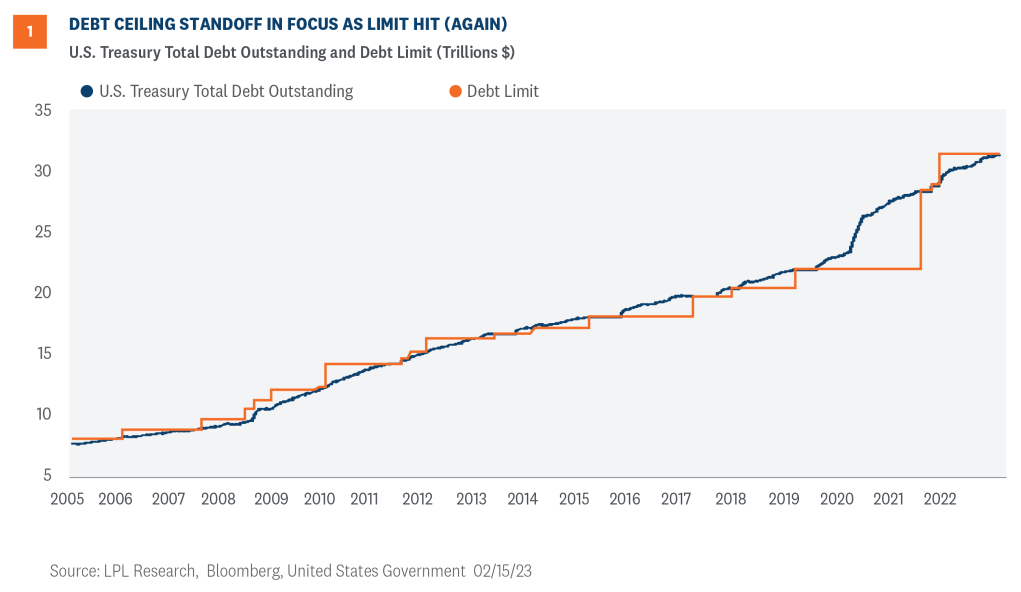

Yes, whenever needed. According to the Treasury, since 1960 Congress has raised the debt ceiling in some form 78 times, 49 times under Republican presidents and 29 times under Democratic presidents. As shown in Figure 1, Congress has regularly raised the debt ceiling as needed. In fact, every president since Herbert Hoover has seen the debt ceiling raised or suspended during their administration.

5. Is the debt ceiling being raised to cover potential new spending programs?

No. Lifting the debt ceiling does not authorize any new spending. The debt ceiling needs to be raised to meet current obligations already authorized by Congress. Theoretically, not raising the debt ceiling would limit spending in the future, but only by deeply undermining the basic ability of the government to function, including funding the military, mailing out Social Security payments, and making interest and principal payments on its current debt.

While perhaps symbolic of excessive spending, the debt ceiling is not the appropriate instrument to limit spending. Spending responsibility sits with Congress and the president, but Democrats and Republicans have both favored deficit-financed spending once in power. Bill Clinton’s presidency, much of it with a Republican Congress, was the only one that saw the publicly held national debt decline since Calvin Coolidge in the 1920s.

6. When was the debt ceiling last raised?

The debt ceiling was last raised in December 2021. No Republicans voted for that increase, but some Republicans did vote to suspend the Senate filibuster so the increase could be passed with a simple majority.

7. If we were at the debt ceiling on January 19 and nothing happened, why is there a problem?

When we hit the debt ceiling, the Treasury is authorized to use “extraordinary measures” that allow the government to continue to temporarily meet its obligations, including suspending Treasury reinvestment in some retirement-related funds for government employees. But the additional funding available through these measures is limited.

8. What’s the actual deadline?

The real deadline, also called the “x date” is hard to pinpoint because it depends on revenue and payments that are variable as we approach the date. The level of tax revenue around the federal income tax filing date is particularly important. The window right now is wide, probably summer to early fall, but that does mean there are circumstances where the actual x date could be early summer.

9. Who typically wins debt ceiling battles?

Independent of anyone’s view on the level of government spending, a timely increase in the debt ceiling eliminates the risk of unnecessary turmoil for markets, businesses, and the economy. As for who wins the battle politically, we leave that for voters to decide for themselves.

10.What would the Treasury have to do if Congress failed to act in time?

Without the ability to issue new debt to pay existing claims, the Treasury would have to rely on current cash on hand (and incoming cash) to make its payments. So, the Treasury would be able to make some payments—just not all of them. As such, the Treasury department would likely have to prioritize its payments. Moreover, the longer the delay in raising/suspending the debt ceiling, the harder it may be for Treasury to make its payments.

In 2011 and again in 2013, Federal Reserve and Treasury officials developed a plan in case the debt ceiling wasn’t addressed in time. At that time, they determined the “best” course of action would be to prioritize debt payments over payments to households, businesses, and state governments. By prioritizing Treasury debt obligations it was assumed the financial repercussions would be minimized. However, given comments by rating agencies (more on this below), there’s no guarantee that prioritizing debt payments would stave off severe, longer-term consequences like a debt downgrade or higher borrowing costs. Nonetheless, in order to adhere to the full faith and credit clause within the Constitution, debt servicing costs would likely be prioritized.

There is the possibility that prioritizing debt service would be challenged in court. Even if there’s a strong case to be made, we think debt service prioritization would be allowed to continue while the case works its way through the courts, since the potential economic damage would be too great otherwise. Even in the very unlikely event that Congress fails to raise the debt ceiling, the political and economic fallout would potentially be so swift that we would expect it to be raised in days rather than weeks or months, making the question of whether debt payments could be prioritized a moot point.

11.U.S. Treasury debt was downgraded in August 2011 because Congress waited until the last minute to raise the debt ceiling. Could we see additional rating changes this time?

In 2011, even though Congress acted before the x date, one of the three main rating agencies, S&P, downgraded U.S. Treasury debt one notch from AAA to AA+. While the other two main rating agencies retained the U.S. AAA rating, they both downgraded the outlook to negative. S&P has maintained that AA+ rating since 2011.

Now, all three rating agencies have publicly stated that they are confident a deal will get done. However, one of the three, Fitch, has threatened to downgrade U.S. debt if the debt ceiling isn’t raised or suspended in time. Further, Fitch has stated that prioritization of debt payments would lead to non-payment or delayed payment of other obligations and “that would not be consistent with an AAA rating.” So even if Treasury made debt payments on time, missing other payments would likely result in a rating downgrade. It is likely other rating agencies would follow suit as well. Another rating downgrade by a major rating agency would likely call into question use of Treasury securities as risk-free assets, which would have major financial implications globally.

12.Could failure to address the debt ceiling push the economy into a recession?

It would depend on how long Treasury would have to prioritize payments. If the delay is only a day or two, then it is unlikely the economy would slow enough to actually enter into a recession. Payments that were deferred would be repaid in arrears so the economic impact would likely be minimal.

However, in the very unlikely event that payment prioritization is necessary over a prolonged period of time—say a month or longer—this could indeed cause economic activity to contract. Since the government is running a fiscal deficit, and since Treasury cannot issue debt to cover that deficit, spending cuts would need to take place. The spending cuts, if prolonged, would likely push the U.S. economy into recession. Moreover, the unknown knock-on effects such as the impact on business confidence would also likely slow economic growth. Since the situation would be unprecedented, it’s very difficult to estimate the impact. Moody’s has said that based on their modeling, “the economic downturn ensuing from a political impasse lasting even a few weeks would be comparable to that suffered during the global financial crisis” (Moody’s Analytics, “Debt Limit Brinksmanship,” 6).

13.How would a technical default impact the financial markets?

In 2011, the S&P 500 fell by over 16% in the span of 21 days due to the debt ceiling debate and subsequent rating downgrade. The equity market ended the year roughly flat so investors who were able to invest after that large drawdown were rewarded. However, that large drawdown was due solely to the policy mistake of not raising the debt ceiling in a timely manner. It’s likely that if Congress were to wait until the last minute in raising/suspending the debt ceiling, equity markets would react similarly.

Perhaps counterintuitively, despite the prospects of delayed payments and the debt downgrade, intermediate and longer-term Treasury yields fell/prices increased as they are generally considered to be a “safe haven” asset. And while that may have been the market reaction in 2011, there is no guarantee that in the event of a technical default and further rating downgrades Treasury securities would have a positive return this time around, particularly if Treasury securities lose their status as the risk-free rate.

Conclusion

Given the experience from 2011, we think it would be prudent for Congress to raise the debt ceiling reasonably in advance of the date when the government would no longer be able to meet all its obligations. Political brinksmanship with the debt ceiling is a dangerous game, with likely relatively little to gain and much to lose. At the same time, we don’t think that should hinder conversations about controlling spending. The debt ceiling simply isn’t the place for that conversation to take place.

IMPORTANT DISCLOSURES

This material is for general information only and is not intended to provide specific advice or recommendations for any individual. There is no assurance that the views or strategies discussed are suitable for all investors or will yield positive outcomes. Investing involves risks including possible loss of principal. Any economic forecasts set forth may not develop as predicted and are subject to change.

References to markets, asset classes, and sectors are generally regarding the corresponding market index. Indexes are unmanaged statistical composites and cannot be invested into directly. Index performance is not indicative of the performance of any investment and do not reflect fees, expenses, or sales charges. All performance referenced is historical and is no guarantee of future results.

Any company names noted herein are for educational purposes only and not an indication of trading intent or a solicitation of their products or services. LPL Financial doesn’t provide research on individual equities.

All information is believed to be from reliable sources; however, LPL Financial makes no representation as to its completeness or accuracy.

U.S. Treasuries may be considered “safe haven” investments but do carry some degree of risk including interest rate, credit, and market risk. Bonds are subject to market and interest rate risk if sold prior to maturity. Bond values will decline as interest rates rise and bonds are subject to availability and change in price.

The Standard & Poor’s 500 Index (S&P500) is a capitalization-weighted index of 500 stocks designed to measure performance of the broad domestic economy through changes in the aggregate market value of 500 stocks representing all major industries.

The PE ratio (price-to-earnings ratio) is a measure of the price paid for a share relative to the annual net income or profit earned by the firm per share. It is a financial ratio used for valuation: a higher PE ratio means that investors are paying more for each unit of net income, so the stock is more expensive compared to one with lower PE ratio.

Earnings per share (EPS) is the portion of a company’s profit allocated to each outstanding share of common stock. EPS serves as an indicator of a company’s profitability. Earnings per share is generally considered to be the single most important variable in determining a share’s price. It is also a major component used to calculate the price-to-earnings valuation ratio.

All index data from FactSet.

This research material has been prepared by LPL Financial LLC.

Securities and advisory services offered through LPL Financial (LPL), a registered investment advisor and broker-dealer (member FINRA/SIPC). Insurance products are offered through LPL or its licensed affiliates. To the extent you are receiving investment advice from a separately registered independent investment advisor that is not an LPL affiliate, please note LPL makes no representation with respect to such entity.

Not Insured by FDIC/NCUA or Any Other Government Agency | Not Bank/Credit Union Guaranteed | Not Bank/Credit Union Deposits or Obligations | May Lose Value

RES-1444214-0223 | For Public Use | Tracking # 1-05361835 (Exp. 02/24)